Sign up for Klimate Insights

Stay in the loop on all things Klimate, carbon removal, and the most important emerging news and policy.

Dive into the latest posts from us.

Check out the most recent news from us around all things carbon removal.

Unlocking the strategic and commercial value of climate reporting

Unlocking the strategic and commercial value of climate reporting

Climate reporting is not just a “nice-to-have” document at the end of the year. Stakeholder expectations are rising, and the gap between ambition and reality is getting easier to spot.

In our recent webinar session, I was joined by Ata Bærentsen (Partner at SustainX) and Molly Baxter (Carbon Consultant at Zevero) to unpack what is driving Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) reporting today, how priorities are evolving, and what it takes to turn reporting into action inside your organisation. Here’s what we uncovered.

What is changing in ESG reporting

1) The move from ambition to credibility

A recurring theme in our discussion was the shift from high-level targets to proving what is actually happening. Many companies have bold commitments. The hard part is showing the plan, the progress, and what it takes to reduce emissions in practice. This means transparency even if—or especially if—progress is not linear.

2) Scrutiny is increasing

We are seeing growing media attention on ESG reports. Journalists (and the public) are getting better at reading disclosures and calling out inconsistencies. One example we discussed was a major Danish company being in the press as emissions continued to grow alongside business growth, even while reduction ambitions stayed high. Proactively addressing these pitfalls and plan to course-correct, backed by trustworthy data, can turn this reputation risk into a cause of credibility.

3) Pressure is coming from multiple directions

Regulation is a clear driver, still including the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD). But, it’s not only regulators. We also see increasing pressure from customers and supply chains, including suppliers being asked to engage through Science Based Targets initiative (SBTi) expectations.

The role of data and tools

If credibility is the destination, data is the route.

Across organisations, ESG data is often spread across teams, systems, and spreadsheets. Ownership is unclear. Definitions drift. And when reporting deadlines approach, the work becomes a scramble.

A simple idea came through strongly: good reporting does not start in the report. It starts with structured, centralised data that is built for repeatable tracking and decision making.

That matters for three reasons:

- it helps you see where emissions sit across your value chain, including Scope 1, Scope 2 and Scope 3 emissions,

- it makes it easier to explain your numbers internally and build confidence in the strategic direction of climate plans, as well as the story you are telling,

- & it reduces the risk of errors and contradictions that can undermine trust.

Where carbon removal fits

Carbon Dioxide Removal (CDR) is becoming a bigger part of climate strategies. Many companies start with nature-based approaches and move towards more permanent carbon removal as they get closer to their net zero years.

But for many sustainability teams, carbon removal is only one part of a much wider plan. Tracking purchases and reporting on them can be complicated, and it can feel like a low reward, high risk activity if the data is not organised.

That is where structure matters most. To report on carbon removal responsibly, you need:

- clear records of what was purchased, when, and why

- consistent documentation you can use in disclosures

- a way to connect carbon removal to your wider decarbonisation journey, without overstating what it does

Without that support, the same action can start to feel risky in terms of greenwashing, or simply hard to explain.

What to do next

If you are trying to turn ESG reporting into something that actually drives progress, start here:

- be clear on what you are reporting for, and who needs to trust it

- agree definitions early, especially for emissions scopes and what sits inside your reporting boundary

- assign data ownership, and build a central place to track progress rather than a last-minute spreadsheet exercise

- treat carbon removal reporting as part of the wider ESG picture, with the same discipline on data, documentation and communication

Reporting is becoming a test of credibility. The organisations that do well will be the ones that make the data usable, the story honest, and the actions measurable.

If you want to listen back to the discussion access the webinar recording here.

Understanding and navigating the reputation crisis in carbon offsetting

Understanding the reputation crisis in carbon offsetting

Carbon offsetting was supposed to be a straightforward climate solution: pay to cancel out your emissions elsewhere. Instead, it has become one of the most contested areas of corporate sustainability, with investigations revealing that many carbon projects deliver a fraction of their promised benefits or nothing at all.

The fallout has left companies facing greenwashing accusations, eroded public trust in carbon markets, and created genuine confusion about what actually works. This article breaks down why the reputation crisis happened, what distinguishes credible projects from questionable ones, and how carbon removal offers a more verifiable path forward.

Why carbon offsetting has a reputation problem

The reputation crisis in carbon offsetting comes down to a simple pattern: companies buy cheap, low-quality credits to claim environmental progress while delaying real emission cuts. Evidence suggests this isn’t an edge case but in fact, it’s been the dominant buying behaviour. One peer-reviewed study that built a company-level dataset of retired credits found that companies predominantly sourced “low-quality, cheap” credits, and that 87% of the credits assessed carried a high risk of not delivering real, additional emissions reductions, with most coming from forest conservation and renewable energy project types. (Nature)

That helps explain why nature-based projects, particularly forest protection schemes, keep becoming flashpoints. Who doesn’t remember the Kariba REDD+ project in Zimbabwe, where reporting documented allegations that climate benefits were overstated and that the project became a major revenue generator for intermediaries, which in return raised hard questions about the credibility of credits used by large brands to support climate claims. (The New Yorker) The result is a market where greenwashing accusations have become widespread, and offsets are increasingly seen as a “get-out-of-jail-free card” rather than a genuine climate solution. After learning what I do for a living, someone recently gave me the now fairly common: “I feel like that’s not working anyway”.

So how did we get here? Why do most people believe the world of carbon offsetting is one big scam? Part of the problem is a knowledge gap. Many buyers lack the expertise to tell the difference between a high-quality project and one that exists mostly on paper. When a company purchases carbon credits, they're often trusting that someone else has done the due diligence. That trust has been broken repeatedly especially when scandals emerge around exactly the kinds of low-cost credits that have historically been easiest to buy at scale. (Nature)

The fallout extends beyond environmental concerns. Companies that invested in what they believed were legitimate climate solutions now face accusations of greenwashing, regulatory scrutiny, and damage to their public image. Offsetting is ultimately a strategy, accompanied by a claim, now associated with low quality credits — smoke-and-mirrors lacking robust evidence. Meanwhile, projects that actually deliver real impact struggle to attract funding as scepticism spreads across the entire market because every new controversy makes the “offset” label itself harder to defend, regardless of quality. (SWI swissinfo.ch)

What is greenwashing in carbon offsetting

Greenwashing… A term we’ve all gotten used to as part of the reputation problem. Greenwashing happens when organisations make misleading environmental claims to appear more sustainable than they actually are. In carbon markets, greenwashing typically involves purchasing cheap credits to claim "carbon neutrality" without making meaningful efforts to cut emissions at the source.

The practice shows up in several ways:

- Misleading claims: Companies overstate the impact of their purchases, suggesting they have "neutralised" their carbon footprint when the underlying credits may have little or no environmental return. The claimed impact of the offset is therefore unequal to the impact of emissions.

- Lack of verification: Buying credits without independent quality assessment or proper due diligence on whether projects actually deliver what they promise. Without providing proper evidence to back a claim, they fall fall short.

- Avoidance over action: Using inexpensive credit as a substitute for the harder work of reducing emissions directly.

When consumers and investors discover that environmental claims lack substance, trust erodes not just in the offending company, but in corporate sustainability efforts more broadly. This is why greenwashing accusations have become such a significant reputational risk.

Key risks that undermine carbon market credibility

Now, it’s important to underline that the risk of greenwashing is there for a reason. Some credits are of a poor quality and there’s a number of technical problems that cause projects to fail. Understanding each one helps explain why so many credits have proven worthless and what to look for when evaluating project quality.

Additionality failures

Additionality means a project would not have happened without carbon finance. If a forest was already protected by law, or a renewable energy plant was already profitable without carbon revenue, then selling credits for that activity generates no additional climate benefit.

The challenge is proving a counterfactual—what would have happened without the project. This is inherently difficult to demonstrate, and many projects have been found to claim credit for activities that would have occurred anyway.

Permanence concerns

Permanence refers to how long carbon stays stored. A tree absorbs carbon dioxide as it grows, but if that tree burns in a wildfire or gets cut down, the stored carbon returns to the atmosphere.

This risk is particularly acute for some nature-based projects. Climate change itself increases the likelihood of fires, droughts, and pest outbreaks that can destroy carbon stores decades before their intended lifespan ends.

Leakage and displacement

Leakage occurs when emissions shift elsewhere rather than being prevented. For example, protecting one forest may simply push logging activity to a neighbouring area that lacks protection.

This displacement effect can negate much or all of a project's claimed benefit. Accounting for leakage requires monitoring beyond project boundaries—something many schemes fail to do adequately.

Baseline inflation

The baseline is the reference scenario used to calculate avoided emissions. If a project claims it prevented deforestation, the baseline represents how much forest would have been lost without intervention.

Inflated baselines lead to credits being issued for reductions that never actually occurred. Some projects have been found to exaggerate deforestation threats dramatically, generating millions of credits for "avoided" emissions that were never going to happen in the first place.

How to identify high-quality carbon projects

Ready to write-off carbon credits as a whole? Don’t worry, there is hope for the market’s reputation as not all carbon projects are created equal. Several criteria help distinguish credible initiatives from questionable ones.

1. Verify third-party certification

Reputable standards like Verra, Gold Standard, and Puro.earth provide independent verification of project claims. However, certification alone is not sufficient and even certified projects have been found to underperform. Look for projects that go beyond minimum certification requirements and provide detailed, transparent documentation.

2. Assess additionality evidence

Strong projects provide clear documentation showing that carbon revenue was essential to their viability. If a project would have happened anyway—through existing regulations, economic incentives, or other funding sources—the credits it generates have limited value.

3. Evaluate permanence guarantees

Check how long carbon will remain stored and what safeguards exist if storage fails. Some standards require buffer pools or insurance mechanisms to address reversal risks, providing an extra layer of protection.

4. Demand transparent monitoring data

Quality projects provide ongoing measurement, reporting, and verification (MRV). This includes regular updates on project performance, independent audits, and publicly accessible data that allows buyers to track outcomes over time.

The lack of transparent data is a root cause of the reputation crisis. When buyers cannot independently verify project outcomes, they rely on trust—trust that has been repeatedly violated by projects that overpromised and underdelivered.

Quality projects openly share their methodology and assumptions, independent verification reports, ongoing monitoring data, and clear impact metrics. This transparency allows buyers to make informed decisions rather than taking claims at face value.

Technology is improving verification capabilities. Satellite monitoring can track forest cover changes in near real-time. Sensor networks can measure soil carbon with increasing accuracy. Digital registries can provide tamper-proof records of credit issuance and retirement. Together, these advances make it harder for low-quality projects to hide behind opaque reporting.

5. Prioritise carbon removal over avoidance

Removal projects offer more certain, measurable outcomes than avoidance-based credits. While removal credits typically cost more, they carry lower risk of the additionality and permanence problems that have damaged the offset market's reputation.

Carbon offsets vs carbon removal

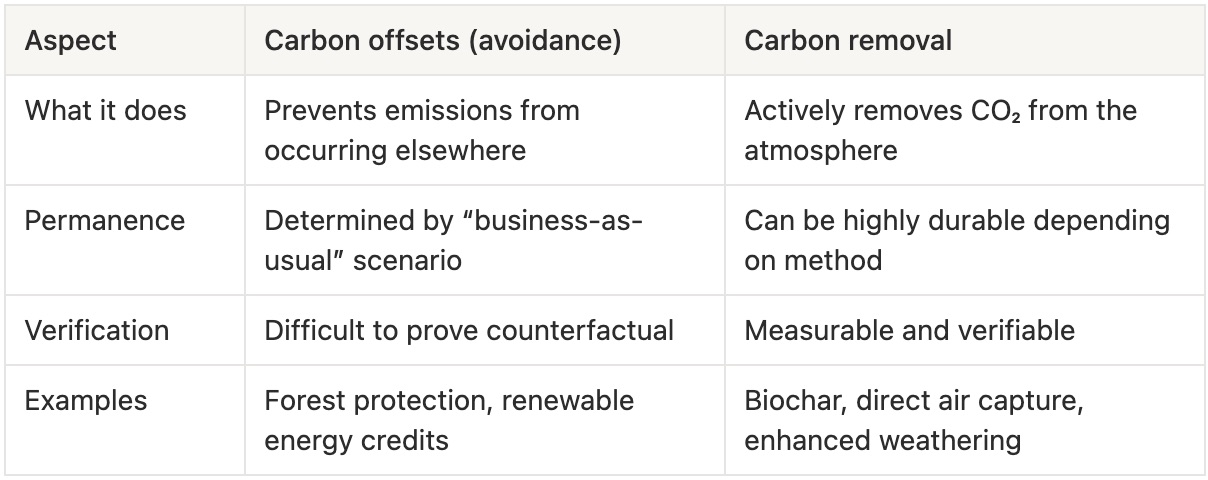

Call me biased, but I want to dive a bit further into the world of carbon removal and how it can deal with the reputation crisis. Understanding the distinction between avoiding emissions and removing carbon is essential for navigating this difficult landscape. The two approaches work differently and carry different risks.

How carbon offsets work

Traditional carbon offsetting involves companies that pay for cheap activities that prevent emissions from occurring to balance-out their own emissions, called avoidance. Protecting a forest prevents the carbon stored in trees from being released. Funding a clean cookstove project prevents emissions from traditional cooking methods.

The challenge lies in proving that the emissions would have occurred without the intervention. This is the additionality problem—and it is why avoidance-based offsets are so difficult to verify with confidence.

How carbon removal works

Carbon Dioxide Removal (CDR) takes a fundamentally different approach. Rather than preventing future emissions, CDR actively extracts CO₂ already present in the atmosphere and stores it for decades to centuries. This addresses the present impacts of climate change and prevents amplified warming due to avoidance creating reductions down the line.

Why permanence matters for climate impact

To truly offset one tonne of carbon, the carbon should be stored for the same amount of time as the emissions released. Durable carbon storage, where carbon is kept our of the atmosphere for centuries or longer, is essential to ensuring long-term climate benefit.

This is why permanence has become a central criterion for evaluating carbon credit quality for companies that plan to offset, and why many organisations are shifting their focus toward removal methods with longer storage timescales.

How companies can avoid carbon credit greenwashing

For organisations seeking to invest in carbon projects responsibly, several principles help reduce risk and build credibility.

1. Prioritise emission reductions first

Carbon credits work best as a complement to direct decarbonisation efforts, not a substitute. Emerging regulations and voluntary frameworks increasingly require companies to demonstrate internal emission reductions before claiming offset benefits. This "reduce first, then offset" approach aligns with scientific guidance on effective climate action.

2. Choose verified carbon removal projects

Investing in CDR rather than avoidance offsets reduces reputational risk and delivers more certain impact. While removal credits typically cost more per tonne, they provide stronger evidence of genuine climate benefit and face fewer of the verification challenges that have plagued traditional offsets.

3. Use independent project assessment

Working with platforms that conduct rigorous scientific evaluation of projects helps identify quality opportunities. Look for partners who assess projects against multiple criteria—not just certification status, but also additionality evidence, permanence guarantees, and ongoing monitoring practices.

4. Communicate climate claims accurately

Avoid over-claiming. Be specific about what offsets achieve versus what internal reductions achieve. Transparency about methodology and limitations builds credibility rather than undermining it. Companies that communicate honestly about their climate strategy—including its limitations—tend to fare better when scrutiny increases.

How science-backed carbon removal rebuilds market trust

The reputation crisis, while damaging, has also driven positive change. Rigorous scientific evaluation, transparent data, and measurable outcomes are becoming the new standard for credible climate action.

High-quality CDR projects demonstrate that carbon markets can deliver genuine impact when built on solid foundations. By focusing on verifiable removal rather than uncertain avoidance, these initiatives offer a path forward for organisations committed to meaningful climate action.

For organisations exploring credible carbon removal options, get in touch to learn about high-integrity solutions backed by rigorous scientific assessment.

Making the investment case for carbon removal: Strategies that work

Why carbon removal investment is a strategic priority

Corporate sustainability has entered a more challenging era. Where sustainability used to be about bold targets and high-level goals, 2026 is shaping up to be a year focused on practical results, risk management and integration with core business priorities. Many companies are already adjusting how they talk about sustainability. As Solitaire Townsend recently noted, the conversation is shifting away from idealistic narratives and towards language rooted in resilience, risk, and long-term value.

Instead of positioning carbon removal as a discretionary climate project, it seems more and more sustainability teams are reframing it as a core element of risk management and future-proofing. For many of us, this shift can feel counterproductive as it moves the conversation away from climate ambition and towards business risk. But the action itself remains just as meaningful — and that is an important point to hold on to.

There is also a clear upside. This framing makes it easier for finance and leadership teams to see carbon removal as a long-term business priority, rather than a peripheral cost. In doing so, it helps sustainability teams make a stronger, more credible investment case.

In this environment, carbon removal is not just another climate initiative. It is a strategic tool that connects sustainability goals with business reality.

What makes carbon removal budgeting challenging

Even when the strategic case is clear, securing budget for carbon removal is still often difficult. Sustainability teams face real, practical barriers when they bring CDR proposals to finance and leadership teams.

- Volatile carbon credit pricing: Carbon credit prices can change significantly over time, making long-term budget forecasting difficult. Many markets operate on spot prices, meaning prices available today may not reflect future costs.

- Difficulty quantifying climate ROI: Carbon removal does not generate a traditional financial return. Its value shows up in reduced risk, stronger credibility, and future readiness, which are harder to translate into standard return on investment (ROI) metrics.

- Competing internal budget priorities: Sustainability teams are often competing with growth, technology, and operational projects for limited funds. Carbon removal can feel abstract to teams focused on short-term financial performance.

- Knowledge gaps among decision-makers: Many executives still do not clearly distinguish between emissions reductions, offsets, and removals. Without this understanding, it is difficult to justify why quality and durability matter, or why carbon removal commands a higher price.

How to build a compelling investment case for carbon removal

This is where framing really matters. A strong internal investment case for carbon removal is less about climate ideals and more about business relevance. As with any communication, the starting point is the audience in front of you and what resonates with them.

1. Frame carbon removal as risk mitigation

Position carbon removal as a way to manage risk. This includes regulatory risk, reputational risk, and long-term financial exposure. Investing in high-quality CDR reduces the chance of future compliance costs, public criticism, or being locked into low-quality solutions that do not stand up to scrutiny. Addressing the fear of greenwashing also matters significantly to leadership. Sharpening data and having transparent progresses around investments are means to avoid greenwashing.

2. Quantify the cost of inaction

Doing nothing also has a cost. Volatile carbon prices, stricter regulations, and loss of stakeholder trust can all carry financial consequences. Comparing the cost of carbon removal today with potential future penalties or lost opportunities helps shift the conversation.

3. Connect investment to regulatory readiness

Disclosure frameworks and climate reporting requirements are evolving quickly and we’ve seen lots of updates in just recent monts to standards like SBTi and CSRD. Early investment in carbon removal helps organisations build systems, data, and processes that will be needed as expectations tighten. This reduces last-minute compliance risk.

4. Benchmark against industry peers

Showing what peers or industry leaders are doing creates urgency. Carbon removal is increasingly part of credible climate strategies across sectors. Falling behind peers can carry reputational and commercial risks.

5. Translate climate impact into business language

Internal conversations land better when they focus on risk exposure, brand value, and stakeholder confidence rather than tonnes of CO₂ alone. Climate outcomes matter, but business language helps decision-makers connect the dots.

Climate language vs business language

Climate language: “We need to neutralise residual emissions.”

Business language: “We need to reduce long-term regulatory and reputational risk.”

Climate language: “This project removes carbon permanently."

Business language: “This investment reduces exposure to future climate liabilities.”

Budget strategies that work for carbon removal procurement

Once approval is secured, the next challenge is structuring the budget in a way that works over time.

Scenario-based budget planning

This approach models different future scenarios, such as low, medium, and high carbon price pathways. It helps teams prepare for volatility and shows leadership that uncertainty has been considered, not ignored.

Multi-year commitment structures

Multi-year agreements can provide price stability and supply certainty. They also demonstrate long-term commitment, which strengthens credibility with stakeholders and project developers alike.

At Klimate, lots of our customers take this approach that shows a commitment to combat climate change but also shows strategic business thinking. One example is Jubel, a UK-based beer brand, that wanted to secure preferential pricing among other goals. A three-year carbon removal strategy gave them that exact solution.

Timing procurement right with the help of a partner

Early commitments can secure better pricing and access to supply, while waiting can preserve flexibility. Each approach has trade-offs. The right balance depends on risk tolerance, budget cycles, and climate targets. Another pathway is to join forces with a partner that takes care of procurement for you and has negotiated the best prices on your behalf.

Why a portfolio approach strengthens your investment case

A portfolio approach means investing across multiple carbon removal methods rather than relying on a single solution. This mirrors how financial portfolios manage risk.

Balancing cost and permanence

Some methods, such as nature-based solutions, tend to be lower cost but store carbon for shorter periods. Engineered solutions are typically more expensive but offer longer-lasting storage. A mix allows teams to balance affordability and durability.

Spreading risk across removal methods

Relying on one method increases exposure if that approach underperforms or faces supply constraints. Diversification reduces this risk and aligns with emerging best practice.

Aligning solutions with corporate values

Different removal methods come with different co-benefits. Some support biodiversity and local livelihoods, while others showcase technological innovation. A portfolio can reflect what matters most to your organisation and stakeholders.

How to ensure quality in carbon removal investments

Quality is central to any credible investment case. Without it, carbon removal risks becoming a cost without value.

- Permanence and durability: Permanence refers to how long removed carbon stays stored. Longer storage periods reduce the risk that carbon returns to the atmosphere and strengthen climate claims.

- Additionality and real impact: Additionality asks whether the removal would have happened without your investment. High-quality projects depend on carbon finance to exist and deliver real impact.

- Transparent monitoring and verification: Robust Monitoring, Reporting, and Verification (MRV) systems and independent verification build confidence in reported outcomes.

- Co-benefits beyond carbon: Environmental and social co-benefits, such as biodiversity gains or community income, add value and strengthen internal and external support.

Making carbon removal part of how the business operates

Securing budget once is hard. Securing it year after year is harder. The teams that manage it tend to focus less on perfect arguments and more on trust, consistency, and internal relationships. They take time to build executive support, not by overwhelming leaders with detail, but by helping them understand why carbon removal matters in the first place. They report progress clearly and regularly, using simple signals that link back to business priorities rather than treating carbon removal as a standalone climate initiative.

Over time, carbon removal stops being a special request and starts showing up in planning cycles, targets, and internal KPIs. In my experience, that shift is often what turns one-off approvals into something more durable.

Having the right partners can also make a difference. When procurement, reporting, and quality assurance are handled transparently, it reduces internal friction and gives finance and leadership teams confidence that the investment is well managed.

Turning commitment into something the business recognises as value

A strong investment case for carbon removal is less about making the perfect climate argument and more about showing how the decision holds up in the real world. It combines clear thinking on risk, confidence in quality, and a practical approach to budgeting that acknowledges uncertainty rather than ignoring it. It also recognises the wider context companies are operating in — changing regulation, tighter scrutiny, and an increasingly complex global environment. Climate action does not sit outside these pressures. It is shaped by them.

If we strip it back, the question of how sustainability teams can ensure budgets for carbon removal and how to make the investment case in-house often comes down to one thing: learning when to speak the language of climate ambition, and when to speak the language of the business.